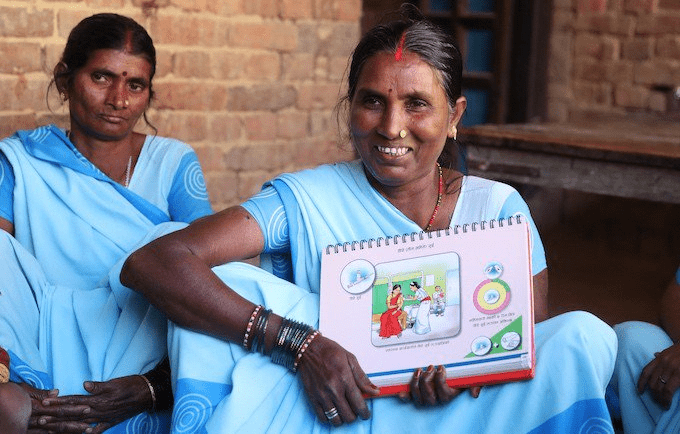

KAPILVASTU – Wearing her volunteer's uniform, a sky-blue sari, Kaushalya Pasi patiently addresses a group of women sitting around her at a village health post in Nepal's Terai region, the western plains bordering India. She points to a flipchart with a picture of a syringe for an injectable contraceptive.

“Do women use this, or men?” Kaushalya asks the crowd. The women stay silent while more of them trickle in, one holding a child in either hand.

“It’s not enough for me to explain,” she tells them. “You need to understand.”

Kaushalya is one of around 52,000 female community health volunteers promoting public health services, including women's reproductive health, across Nepal. Data from UNFPA’s State of World Population 2019 report show that the country has a contraceptive prevalence rate of 54 per cent among women who are married or in a union, and a 22 per cent unmet need for family planning.

The work is even more challenging in Muslim communities like Gauri, a village of over 2,200 people in Kapilvastu District which just two years ago had a contraceptive prevalence rate of only 26 per cent, according to the health post. In Kaushalya’s experience, most households there oppose contraceptive use because their “maulanas”, or Muslim religious leaders, had told them it was “haram”, or against Islam.

But these attitudes have been slowly changing since 2017, when a UNFPA project, funded by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID), began to support local volunteers in their efforts to show families the benefits of voluntary family planning.

The project helps local organizations send prominent maulanas and social leaders from Kapilvastu District to Indonesia, the country with the world's largest Muslim population. There, they meet with Islamic scholars who teach that using contraception in most cases is compatible with the Koran.

Returning religious and social leaders have come out in support of voluntary family planning – at first furtively, Kaushalya says, and later more openly.

to friends and neighbors about their experience. ©UNFPA Nepal

Spousal, family consent

Even though religious leaders have endorsed family planning, individual households are not yet aware that women should be empowered to advocate for their own needs, and some men doubt that family planning is a woman’s right. In fact, many husbands refuse their wives’ wishes to stop having kids.

“Women told us that their husbands might kill them if they used contraceptives without their consent,” she says. Kaushalya and her colleagues then decided to go door-to-door to persuade husbands and mothers-in-law that family planning would help them better provide their children with decent clothing, food and education.

Although families came around, many women did not yet trust contraceptives. To dispel rumours that women would feel weak or get sick, volunteers encouraged women who were already on contraceptives to talk to friends and neighbors about their experience, for instance using injectable contraceptives, the first and still most popular option in Gauri.

One of these endorsers is Sadida Khatun, who approached Kaushalya about using oral contraceptive pills as a convenient temporary measure.

“After I started using them,” she says, “I took neighbors to the clinic, and they started taking pills too.”

Women like Sadida now regularly seek Kaushalya's advice, and she feels the stigma of using contraceptives has weakened. Women who used to feel embarrassed to show their arms after getting a shot now go the clinics openly.

The last remaining obstacle is for women to gain full control over their own bodies. Many still need approval from multiple family members to receive contraceptives, and are often chaperoned by in-laws.

“I hope that in the future,” Kaushalya says, “they’ll be able to go alone.”