At first, Anita Yadav just listened.

She sat quietly at the back of the Adolescent-Friendly Information Corner (AFIC) at Tilaurakot Secondary School, where she studies in Grade 10. The posters on the wall—about menstruation, consent, and reproductive health—felt unfamiliar, even uncomfortable. But the room was calm. No one laughed when someone asked a question. The teacher didn’t scold or skip over anything. So, she stayed.

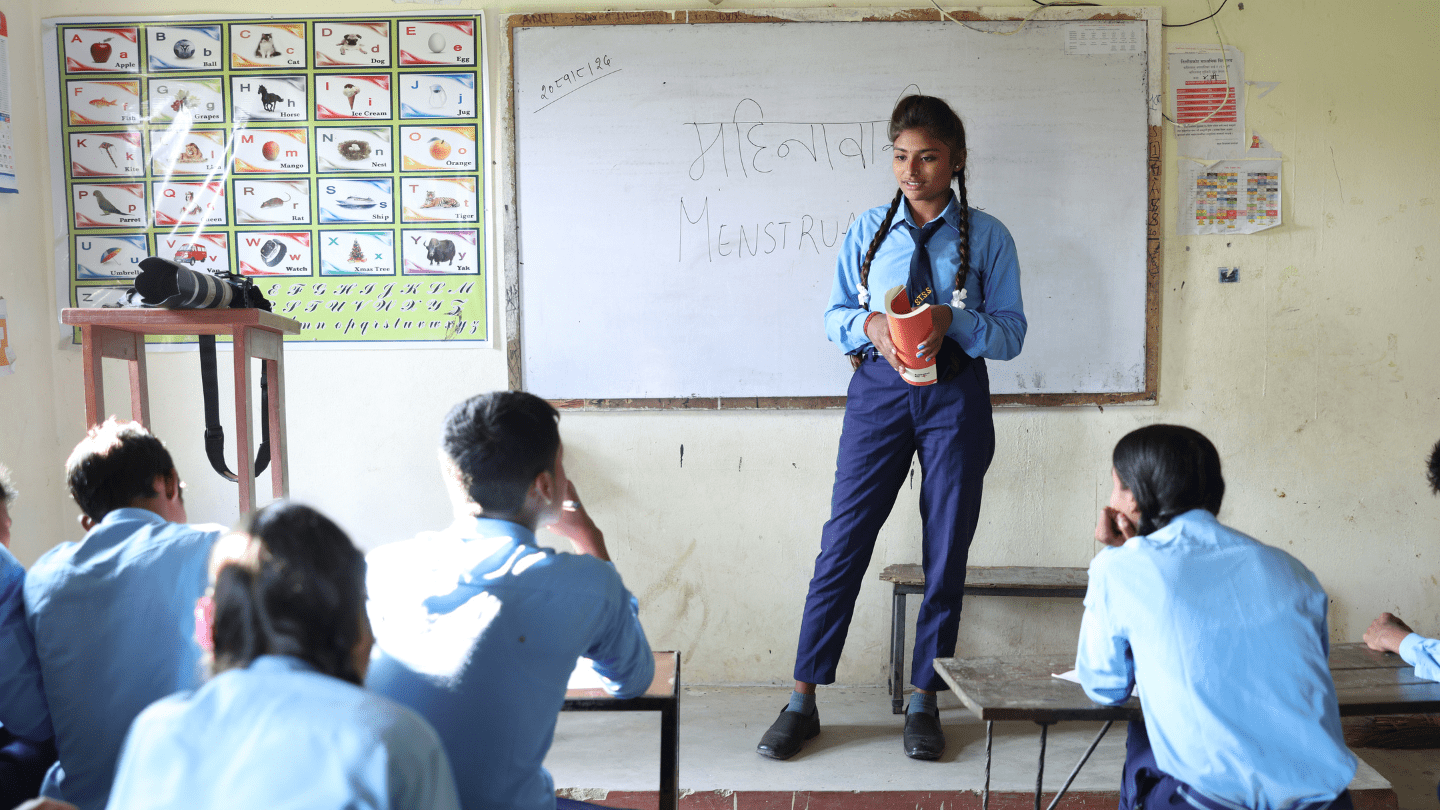

A year later, Anita is one of the most active students in her school’s AFIC.

Her small world—comprised of two brothers, farming parents, and a home she shares with her grandparents—has not changed. But Anita has. And that change started when she realized she was allowed to be curious.

“I didn’t know it was okay to say these things out loud,” she says. “But now, it feels strange not to.”

The AFIC is a quiet room tucked into a corner of her government school in Kapilvastu. There’s carpet on the floor, charts with handwritten notes pinned to the wall, and shelves stocked with information booklets and sanitary pads. It’s part of a larger effort led by UNFPA and the Department of Foreign Trade and Affairs of the Australian government to introduce Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) in public schools. Through this initiative, adolescents—especially girls—are learning about their bodies, their rights, and how to speak for themselves.

Anita remembers a time when asking for pads at school was unthinkable. At home, she avoided even mentioning she was on her period. “We weren’t allowed in the kitchen during that time. We weren’t supposed to touch certain foods,” she says. “At school, I started to learn that none of that was necessary. But I didn’t know how to explain it at home.”

That changed after she brought home a CSE booklet from the AFIC. At the dinner table, she began gently raising what she had learned. Her grandfather frowned. Her mother didn’t say much. But the next time she had her period, a small bowl of warm milk was left at her bedside. Nothing was said—but the message was clear.

“I didn’t argue with them,” Anita says. “I just told them what I was learning. Slowly, they started listening.”

Now, Anita helps other girls in her class access information and services from the AFIC. When someone misses school during their period, she checks in. She’s also learned how to talk to boys in her class about menstruation—without embarrassment or fear. That confidence didn’t come overnight. But it came.

She’s not sure what she’ll do after school, but she knows she wants to work in health. “Maybe as a nurse. Maybe teaching girls like me,” she says.

Across the country, more than 27,000 adolescents like Anita accessed AFICs in 2024. Each of them brings the programme into their own homes and communities in different ways. In some places, it leads to families abandoning harmful taboos. In others, it means girls going back to school—or not getting married too soon.

For Anita, it meant asking questions, and not backing away from the answers.

“I used to think I should stay quiet about certain things,” she says. “Now I think: if we don’t ask, how will anything change?”

At home, the change is visible in small but meaningful ways. Her mother, Sunita, who once quietly followed household taboos around menstruation, now speaks openly with Anita about what she’s learning in school. She’s started setting aside vegetables and eggs for her daughter during her cycle, something that would have been unthinkable just a year ago. Even Anita’s grandfather—stern and traditional—has softened. He no longer questions why Anita stays inside the kitchen during her period, and once, when she was unwell, reminded her to drink warm water and rest.

“They still don’t say much,” Anita says with a smile. “But I can feel the difference. They’re listening now.”