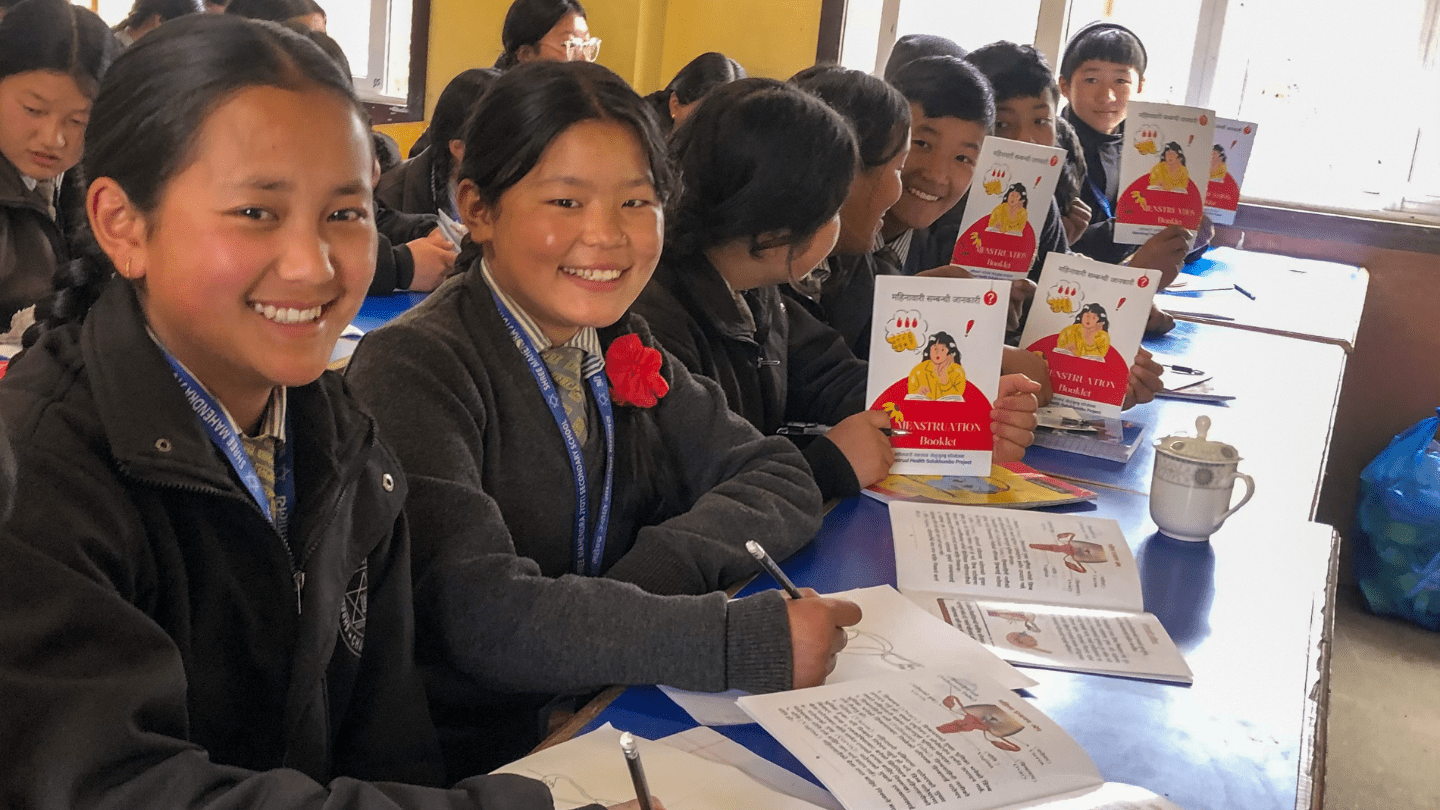

In the remote district of Solukhumbu—where access to essential menstrual products is limited by distance, affordability, and harsh weather—UNFPA introduced a menstrual health support kit (MHSK) consisting of reusable menstrual cups and period underwear, alongside a comprehensive menstrual health education program. The initiative sought to equip adolescent girls with sustainable menstrual products and the knowledge to manage their periods safely and with dignity.

For students like Lhakpa Chhongi Lama, a Grade 9 student at Junbesi School, this support arrived like a lifeline.

“Living in the Himalayas, accessing menstrual products is very difficult,” Lhakpa says. “Even when available, they’re expensive and of poor quality. I often get rashes from the pads we buy locally. There’s no place to dispose of them, so we burn them—which isn’t good for our health or the environment.”

Before this program, no such initiative had ever reached her school. “I remember being scared and confused during my first period. I didn’t have the right information, and the school toilets weren’t clean enough to manage my periods properly.”

After attending the menstrual health sessions and receiving new products to try out, Lhakpa says she feels more confident and prepared. “I had never heard of period underwear before. It’s not sold in our local markets. I felt lucky and excited to try it. Now I’m more comfortable talking about menstruation, and I understand how my body works.”

For Mingma Sherpa, also in Grade 9, the intervention transformed a painful memory into a story of learning and empowerment.

“When I got my first period, I thought I had a disease,” she shares. “I didn’t tell anyone—not even my mother. I used old rags secretly and was scared someone would find out.”

It wasn’t until her second period that she finally opened up. “My mother explained what was happening and gave me a cloth pad. I wish I had talked to her earlier—it would’ve saved me so much fear.”

Mingma notes that while the school provides disposable pads, many girls, including herself, feel shy asking male teachers for them. “The program helped me realize I’m not alone. Now I know it’s okay to ask questions, to speak up, and to take care of myself.”

The impact was just as visible to educators.

Sarita Adhikari, a teacher at Junbesi School, witnessed first-hand how the program shifted school culture.

“Before, students used to leave class saying they were sick or giving vague excuses—later we’d find out it was due to their period. They felt too ashamed to say it outright.”

But after the MHSK program, Sarita saw a change. “Students started speaking openly, asking questions, supporting each other. There’s a new confidence among the girls.”

Yet challenges persist. “Students walk long distances to get to school, there are no pharmacies nearby, and the products we do have are costly. During the monsoon, getting to the shop is almost impossible. And we don’t have basic things like hot water bags, rest rooms, or pain relief in school.”

She sees great value in the reusable kits. “The girls love period underwear. It’s easy to use, comfortable, and better for the environment. But it’s not available locally. We really hope these products can be made more accessible again.”

She believes more can be done. “If we could teach students how to make their own cloth pads with support from the local government, it would be affordable and sustainable. And if programs like this reach students from Grade 6 to 10, the dropout rate among girls will go down. There will be real change in their lives.”

The MHSK project in Solukhumbu was a small pilot—but its impact has been anything but small. For many girls in Nepal’s mountain districts, it marked the first time someone acknowledged their experience and offered real, practical support. The stories from Solukhumbu reflect what happens when dignity meets access, when education is paired with empathy, and when periods are treated not as a source of shame—but of strength.